Culled From Businesstimes

Six years ago, Aliko Dangote paid a visit to Tanzania, on Africa’s eastern coast, and shared his dream of having an African-run business empire that would manufacture products all over the continent. To assorted government and business leaders, he announced that he was prepared to make an investment of $600 million to build a cement factory in southern Tanzania, alleviating the shortage in that country’s domestic cement supply. The Tanzanians were skeptical. “They didn’t believe us at all. They thought I was one of these ‘Nigerian 4-1-9’ scammers who try to go and scheme people out of their money,” Dangote says. “Or just one of these clever Nigerians who would come and be lying to them.”

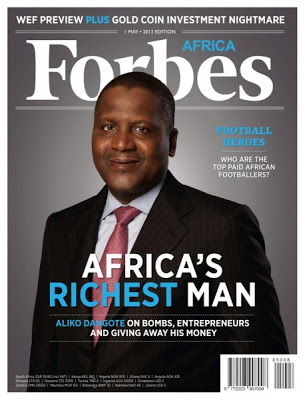

The Tanzania story is clearly one Dangote relishes telling—not least because of how it’s turning out. Not long after his visit, his name appeared on a list of the world’s wealthiest people, and the Tanzanians realized they had been negotiating with Africa’s richest man. As founder and chairman of Dangote Group, he’s worth an estimated $16.3 billion, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index. “They pieced the two together,” Dangote says, sitting in his expansive Lagos office in late January. The room is so gigantic it appears nearly empty, even with tall plants, a conference table, and a large-screen television. Three months ago, Dangote Cement signed a final agreement there, with plans to produce 3 million tons of cement a year.

Dangote Cement is Africa’s largest cement manufacturer; the Dangote Group employs 26,000 people in Nigeria alone. The company is constructing cement plants in Ethiopia, Zambia, South Africa, Senegal, Cameroon, the Republic of Congo, and several other African countries. “We want to be predominately in sub-Saharan Africa, and then we will move out of Africa,” he says. He announced plans last fall to construct plants in Iraq and Burma.

Dangote Group also mills flour, processes salt, produces fertilizer and pasta, and has big plans for sugar. The Nigerian sugar refinery, located at the port of Lagos, is the second-largest in the world. “The same revolution that we’ve had in cement, we want to replicate in sugar,” says Dangote, referring to his push to increase domestic production of a legacy import.

Despite being one of the world’s top producers, Nigeria has yet to refine its own oil. Dangote wants to build a $7 billion facility that would annually process 400,000 barrels of petroleum. “When you look at most of what we’re consuming today, these are things that are being imported,” Dangote says. “We want to make sure that our people are self-sufficient in terms of producing more. The market is there for us to take, but the production is not there.”

Because of his success and vision, his partners, friends, and admirers hold Dangote up as the face of the new Nigeria. With corruption on the wane and the economy liberalizing, Nigeria, they say, is safer than ever for foreign investment. And Dangote’s profile does appear to be contributing to greater confidence in the country. Goldman Sachs (GS) included Nigeria in its Next 11 list of the most promising 21st century economies, and Citigroup (C) called it a “3G,” one of its “global growth generators,” countries with growth potential and investment opportunities. Dangote’s critics—who are not hard to find, if reluctant to speak publicly—say he hasn’t created a model for the future but simply found a way to play a still-rigged game better than others.

Dangote, 55, is a household name in Nigeria and is seen as both a son of privilege who benefited from family connections and a striver who has earned his unprecedented wealth. A workaholic—other businessmen gossip that he rarely sleeps and never vacations—he spends about half his time in Nigeria and the rest traveling around the world. He’s married with three adult children.

“He’s charming and humble, but he’s hard to pin down,” says Theresa Okeke, the American director of Lagos’s Civic Centre, a recreational center for the well-to-do. He’s also a favorite among the moneyed set that circulates through the polo and boat clubs and extravagant mansions of Ikoyi and neighboring Victoria Island, enclaves separated by a bridge from the rest of Lagos. (Recently, the French liquor brand Veuve Clicquot said it plans to open an office in Lagos; some upper-class Nigerian families like to hand guests their very own yellow-labeled Champagne bottle at parties.)

!["You're A Greedy, Heartless, Wicked President" - Nigerian Lady Slams Tinubu [Video] 12 "You're A Greedy, Heartless, Wicked President" - Nigerian Lady Slams Tinubu [Video]](https://media.kanyidaily.com/2025/03/26110211/Tinubu-150x150.jpg)

![Oby Ezekwesili Shares Her Account Of What Led To Her Clash With Senator Nwaebonyi 14 Ezekwesili Shares Her Account Of What Led To Her Clash With Nwaebonyi [Video]](https://media.kanyidaily.com/2025/03/26101440/Ezekwesili-Nwaebonyi-150x150.png)